Jessie Li: Temporary Tenants - A Review by Kelly Loughlin

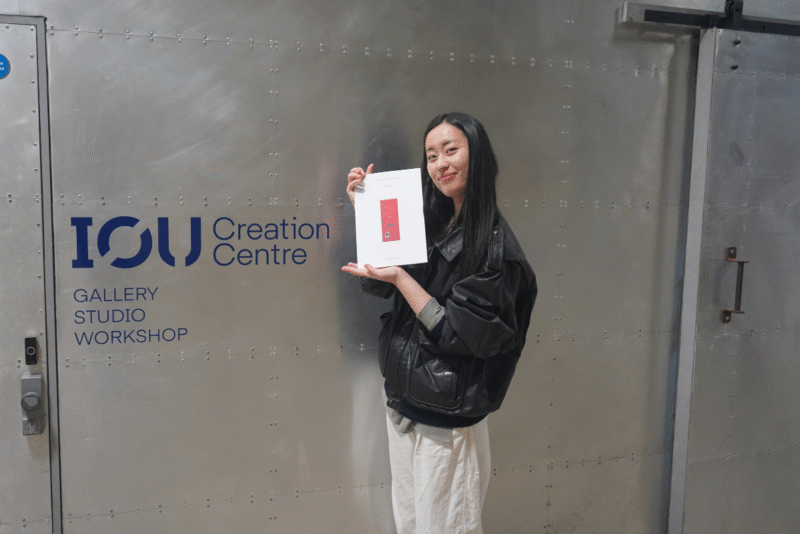

Exhibition exploring memory and moving - what we take and what we leave - through the items and stories gathered during her time as IOU Artist in Residence.

Jessie Li: Temporary Tenants

IOU Creation Centre, Dean Clough, HX3 5AX

Exhibition Open to View:

Monday to Friday – 8am – 8pm

Saturday & Sunday 9am – 5pm

Free Entry. Suitable for all ages.

+ Free parking at weekends

How to visit the IOU Creation Centre

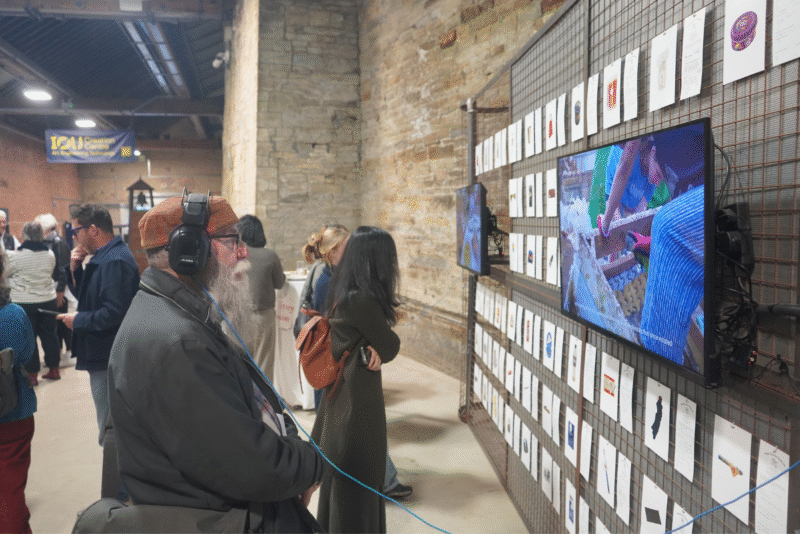

Temporary Tenants occupies the Walkway Gallery at IOU Creation Centre, a busy thoroughfare, which mirrors the kind of impromptu, street level encounters that sustain Jessie Jiaqi Li’s practice.

The show includes a book, audio-visual work and a photographic archive of donated objects, supported by written records, informal receipts. Also present are props found and re-worked for interactive performance, an abandoned shopping trolley refitted as ‘Free Corner Trading Trolley’, and a table re-shaped as a mobile ‘Second-Hand Story Kitchen’, complete with a choice of menus.

Li’s a graduate of the MA in Situated Practice at The Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL), which suggests a multidisciplinary practice, site-specific and experimental in its approach to social contexts. The work on show in Halifax emerged from Li’s six-month residency at IOU’s Hostel in Hebden Bridge, a space of temporary residence where those passing through can be there for as little as one night.

Temporary Tenants is a neat fit with the artist’s location in a hostel, but it goes deeper. Originally from China, Li navigates visa requirements to study and work across borders, moving from residency to residency developing her practice, operating in a second or third language.

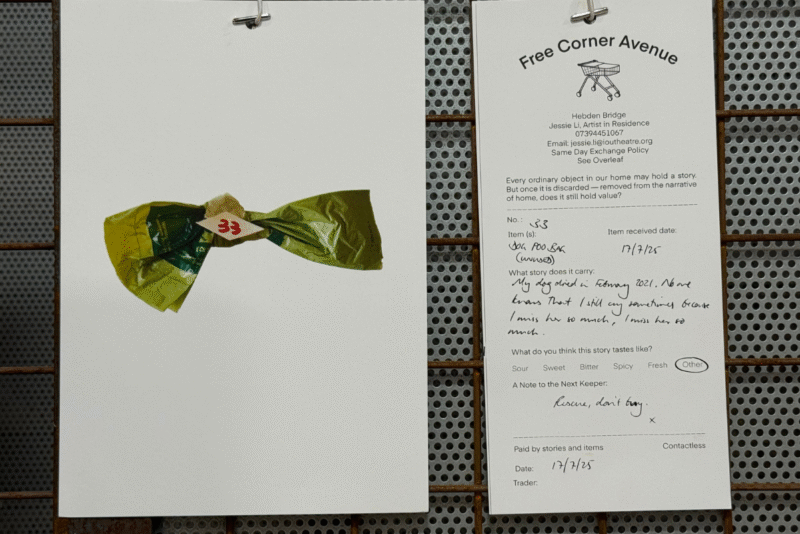

I spoke with Li about working across language; the text of the book is English and Chinese, one video narrated in English, one in Chinese. For Li this is another facet of the provisional, “I’m only a temporary tenant in English. I’m not settled”. There’s a sense of movement in the work, a quiet ebb and flow of people and things; the stuff of our lives dispersed, given-away, or once treasured things left behind as life moves on. Solitary objects and scraps of ephemera are presented as an archive of photographic portraits. Relevant documentation is displayed alongside the images, printed receipts where each donor has recorded a memory of the object, written notes for the new owner; objects and people inked by paper-trails, indexing protocols.

In the video work we encounter some of the people behind the objects. Residents of a street adjacent the Hostel, Chapel Avenue, and the site of the ‘free corner’, a collection of things left at the street corner.

It’s a spontaneous recycling scheme, aimed at extending the useful life of items by passing them on. Conversions open-up and Li builds relationships with her temporary neighbours. They recount stories of their time in the house and the belongings that hold memories for them. Gathering things and the stories attached to them, Li creates her mobile, shopping trolley version of the ‘free corner’, and takes to the streets on Halifax and Hebden Bridge, trading things and stories in areas of exchange, conviviality, marketplaces, shopping districts.

Li’s work develops further as she puts the shared memories into circulation. Fashioning an old table into the Second-Hand Story Kitchen, a point of encounter and performance as she makes her way through Halifax streets. People approach, order a story from a range of menus, Love Stories, Moving Stories. It’s a system of exchange which supports connection, entanglement rather than severance. The printed ‘bill’, when it arrives, asks for payment in the form of a story.

In the performances Li wears a white service coat, suggestive of catering or food handling. I ask about the use of pop-up food and takeaway elements in her work.

She highlights the importance of food as a familiar ritual of interaction. In a previous project she developed a Chinese Takeaway, adding performance into everyday encounters in a space that’s familiar but different.

Another element of Li’s practice comes to the fore in the video piece narrated in Chinese with English subtitles. We follow conversations between Li and Lin, a Chinese woman renovating a house in Hebden Bridge. Bought at auction the house is full of the previous tenant’s belongings; everything is there, an entire life. The lengthy process of sorting and clearing affords a sense of the missing man, his size, weight and the way he walked; revealed by a built-up shoe. As we follow the new tenant through room after room, we begin to sense how the house and its belongings still hold the shape of the absent tenant.

As we talk about the video Li recollects a house clearance she witnessed in Limehouse, London’s first Chinatown. An elderly man had passed away, and the clearance team assembled the contents of his home on the pavement, “… everything, his entire life. It was an archive on the street”

We discuss the relations between objects, spaces and memory, and this leads us naturally to Bachelard’s classic text The Poetics of Space (1964), the idea of spaces, especially domestic spaces as archives of memory, the home as a storage devise, a container that holds time.

There’s a lightness to Li’s practice. We see this in the ease with which she creates encounters and connections on the street. But there’s also a depth, hinted at in the layers and contemporary urgency we sense in the phrase ‘Temporary Tenants’.

Kelly Loughlin

Oct 2025