'What We Do In Public' by Kelly Loughlin

A Review of the CalderdaleCreates and IOU Creation Centre's Art, Nature and the Public Realm Symposium

July 17 2025 Art, Nature and The Public Realm Symposium

In bringing together artists, producers and organisations to explore art in public spaces, this one-day symposium felt like the start of something, and I hope there’s more to come.

Commissioned by Calderdale Creates and delivered by IOU Creation Centre, the event took place across the historic Birchcliffe Centre and IOU Hostel in Hebden Bridge.

Participants moved between panel discussions and readings in the main hall of the Victorian chapel, to more low-key sessions exploring mindfulness and meditation, botanical archives, and artistic methods used in eco-social practice.

Jessie Jiaqi Li, the Hostel’s artist in residence presented work developed over a six month period in Halifax and Hebden Bridge.

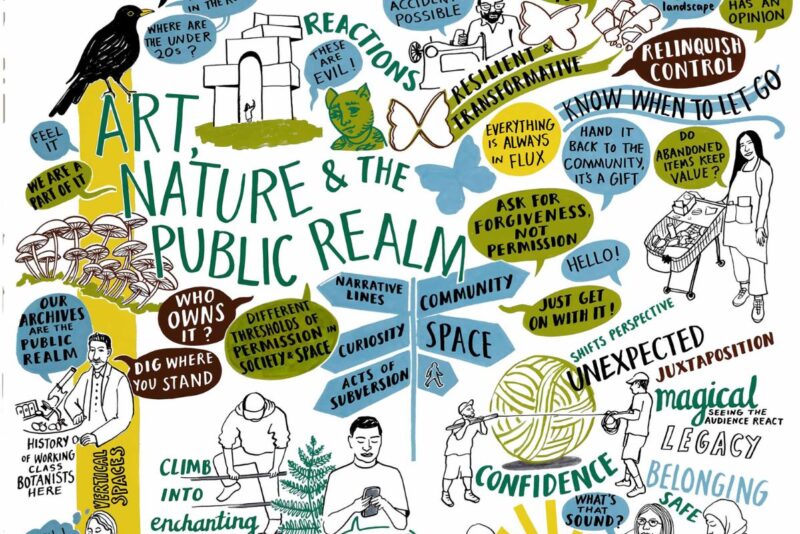

Proceedings in the main hall were captured live by Claire Stringer’s beautiful visual notes. Throughout the course of the day Claire produced wonderful visual minutes of the symposium. Her illustration helped to capture the conversations, ideas and questions emanating out of the days discussions.

The weighty title Art, Nature and the Public Realm felt deliberate, a provocation almost, as these are undoubtedly big, gnarly concepts. In practice, and as the contributors demonstrated, artists constantly push, stretch and blur the edges of such concepts.

‘Public realm’ has a long association with the city. And in her opening address, Creative Director of Bradford 2025 City of Culture, Shanaz Gulzar, spoke of Bradford’s unique bid as a ‘city and district’ that is two-thirds rural. As the day unfolded, I was struck by the way artists moved seamlessly between urban and rural in developing creative possibilities – whether bringing work shaped by the natural world into urban settings, or developing work in remote, even protected landscapes.

As discussions and conversations progressed, we spoke less about public realm and more in terms of ‘space’; of making and holding space for artists to produce work (Catherine Waddington, Kerenza McClarnan, Kate Harvey) and the way outdoor art in particular produces ‘social space’, creating sites of interaction and conviviality.

Allied to this were conversation about access and the necessity of always asking the question – who isn’t in the space? Many buildings and urban centres meet certain accessibility requirements but how does this work in rural settings?

The necessity of partnership working, building strong collaborations across sectors emerged as a key to making things happen on the ground, securing permissions etc, and possibly supporting access needs too.

Artists Trudie Entwistle, Dan Fox, Vanessa Da SIlva and Shanaz Gulzar spoke of the importance of a light touch when situating work in sensitive or protected sites. I was left with an image of work made from the landscape, exposed to time and the elements, then slowly returning back to the landscape.

I was struck also by Dan Fox framing his practice as a travelling fair, a temporary structure that appears and leaves no trace, light and sound installations opening-up unique but fleeting social worlds that are low-impact, off-grid.

Movement was a key theme across the day, from light trails and audio-walks, to floating theatre on the Rochdale canal. The centrality of creative journeying responding perhaps to global movement, migration, displacement; journeys by foot, by water, augmented, immersive, tracked. Here, it’s worth noting Artichoke’s contribution, working at scale and delivering a sense of intimacy and connection in epic public processions.

Artists spoke of responding to a site and its histories (Vanessa Da Silva), or responding to encounters with the more than human, Wolfgang Buttress coproducing work with bees and celestial bodies; poets and writers speaking with-and-for peat bogs (Clare Shaw & Anna Chilvers).

These and other contributions touched upon questions of vulnerability – the vulnerability of our landscapes and ecosystems. This was evident in Trudie Entwistle’s work as an artist developing natural flood management as part of her practice. And evident too in relation to the vulnerability of our communities and a desire to change narratives about place (Parvez Qadir).

Speakers from the floor also raised questions about the vulnerability of artists, in particular the lack of support often experienced by freelancers working in large organisations, and the emotional load of working alongside marginalised communities only to leave these people behind as you move on to the next commission.

I’d suggest there’s a tension here that will benefit from further exploration at the next get-together. A tension between the desire for a light touch when working in nature, and the very different, often transformative relationships that emerge through socially engaged practice with communities.

Clearly, many artists work with landscapes and communities, there is no neat distinction here. But the contributions from the floor highlight the importance of care, and the need for an ‘ethics of practice’ that includes artists, as well as the landscapes and communities we work alongside. A striving for sustainability has emerged as a key element in organisations and across creative practice. But we still need to model what a sustainable freelance practice looks like for an individual artist.

What I found particularly striking about the day was the presence of a rich history in the room. A real sense of time spent in the field, and a gathering of practitioners who have weathered the shifting policy landscape of the last half-century. Our hosts, IOU, are about to turn fifty and they’re currently developing their archive as a creative resource for the future. This development circles us back to the first session of the day and discussions about the ‘public realm’, because archives are an essential part of public space. Local archives are sites of engagement and public participation in ongoing discussions about place, identity and belonging. A great example here is Sheffield’s Dig Where You Stand, an artist-led initiative for archival justice that uses historical records to challenge mainstream migration histories.

As artists we tend to focus on how to move forward. Whereas the archive asks us to stop, re-think and challenge the present. This was the idea behind the Symposium’s lunchtime activities – a pause, meditative, reflective. I presented archival material from a local working-class botanist active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This material offers a record of ordinary people, looking, searching and noting down the flora and fauna across time. It presents models of learning, participation and organising that seem remarkable from where we stand now.

Cultural archives are not that different from any archive in the sense they document change over time. I imagine IOU will offer an archive rooted in place, the Calder Valley, a local archive that’s also an archive of practice and participation that stretches beyond the UK. The collection will document ways of working and organising, some of which will seem impossible to artists entering the field today. And this is precisely why we need to re-acquaint ourselves with the archives of organisations like IOU and Welfare State International, because we need records of audacity, invention and public joy.

Kelly Loughlin

Oct 2025